The Seeds of the Invisible in the Visible World

Tuesday, February 5, 2013

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

Oh the Glory!

Comic generators always seem like great ideas. The pictures look nice, and there appear to be endless options for modification...until I try to make changes. I am limited to flipping images, rotating them, and drawing with my finger or a mouse on a screen. While I can get a perfectly passable comic, I don't really get to use my ideas about design. It's almost always a good idea to draw some of your comic.

There's my pitch.

Now, I'll talk about some of my design considerations in this brilliant, thoughtful comic. [New Pulitzer category: Pure Effing Genius]

I didn't want anything to be quite centered because that shows stability, and this comic is about instability of the mind. I used a lot of diagonals to show movement and tension. In the second panel the diagonal is clearly about tension, and in the fourth panel it's about movement.

The bottom of a panel is heavier and sadder while the top signifies happiness or triumph. I played with this idea in panels two and four. In two, the face is low and sad, and what's high seems to follow (left to right reading) from this negative frame of mind. However, it's not positive. In panel four, I stuck with the left to right reading pattern, but I made the fever dream of alcohol and turkey a positive thing that leads to a rainbow-flooded haze of tranquility. I also wanted the dynamic panel four to contrast with the static starting place of panel one. Panel one is a little off center to suggest instability and also the edges/corner of the picture world. This state of grumpily looking at a computer has been going on for a long time.

Ready for the silly part? No, we hadn't already covered that.

Panel three is how I would represent a manic prayer. The upper part of the panel is hope and potential, and the lines, that in retrospect look like steam or smell waves, are diagonal and wavy because it's not so much a thing said but a hope just boiling out of the pores.

Right.

So, enjoy your comic and design, and have a safe Thanksgiving!

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

With apologies to Marjane Satrapi

| Nosferatu is watching you! |

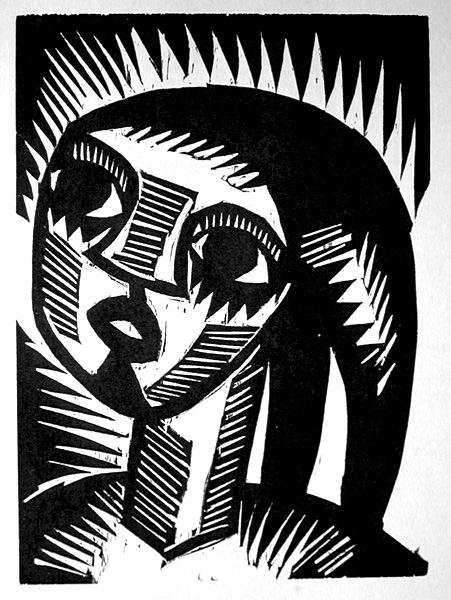

I have been feeling bad about my critique of Marjane Satrapi's skills as an artist. Maybe it's a fear that I'm being influenced by the bias against women in comics. Maybe it's that I find myself moved by some of her drawings as well as being put off by them. So, the subject of this blog post will be about Satrapi's artistic style. Let's start with what Satrapi admits about her style. First, she cites German expressionism; in particular, she notes the "games" with black and white that we see in Murnau's 1922 film, Nosferatu (which is just, hands down, the scariest vampire EVER).

I've also included other images from German expressionism, mostly woodcuts, which was popular at that time. Stylistically, Persepolis looks like it could have been made with woodcuts.

I've also included other images from German expressionism, mostly woodcuts, which was popular at that time. Stylistically, Persepolis looks like it could have been made with woodcuts.Satrapi says:

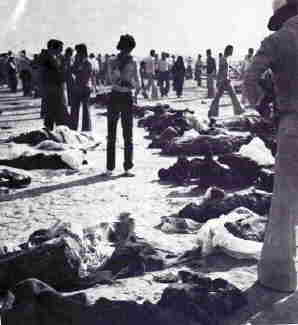

"I write a lot about the Middle East, so I write about violence. Violence today has become something so normal, so banal-that is to say everybody thinks it's normal. But it's not normal. To draw it and put it in color-the color of flesh and the red of the blood, and so forth-reduces it by making it realistic"

The underlining is mine. To understand this, I think we need to go back to our good friend, Scott McCloud. The more iconic a character is, he argues, the more we are able to see ourselves. Does the same hold true for situations? Are we more able to see the horror of the Rex Cinema burning on page 15, where 400 people were locked inside a burning building where they died if it's more iconic?

This picture shows us what a child would imagine of this event: skeletons floating up to the sky, but that same child-like simplicity may portray the event with special brutality and force. Here are some photos from the time:

This picture shows us what a child would imagine of this event: skeletons floating up to the sky, but that same child-like simplicity may portray the event with special brutality and force. Here are some photos from the time:

I don't know. I think Satrapi's expressionist style does a pretty good job.

Here's Satrapi again about her style and the violence she was depicting:

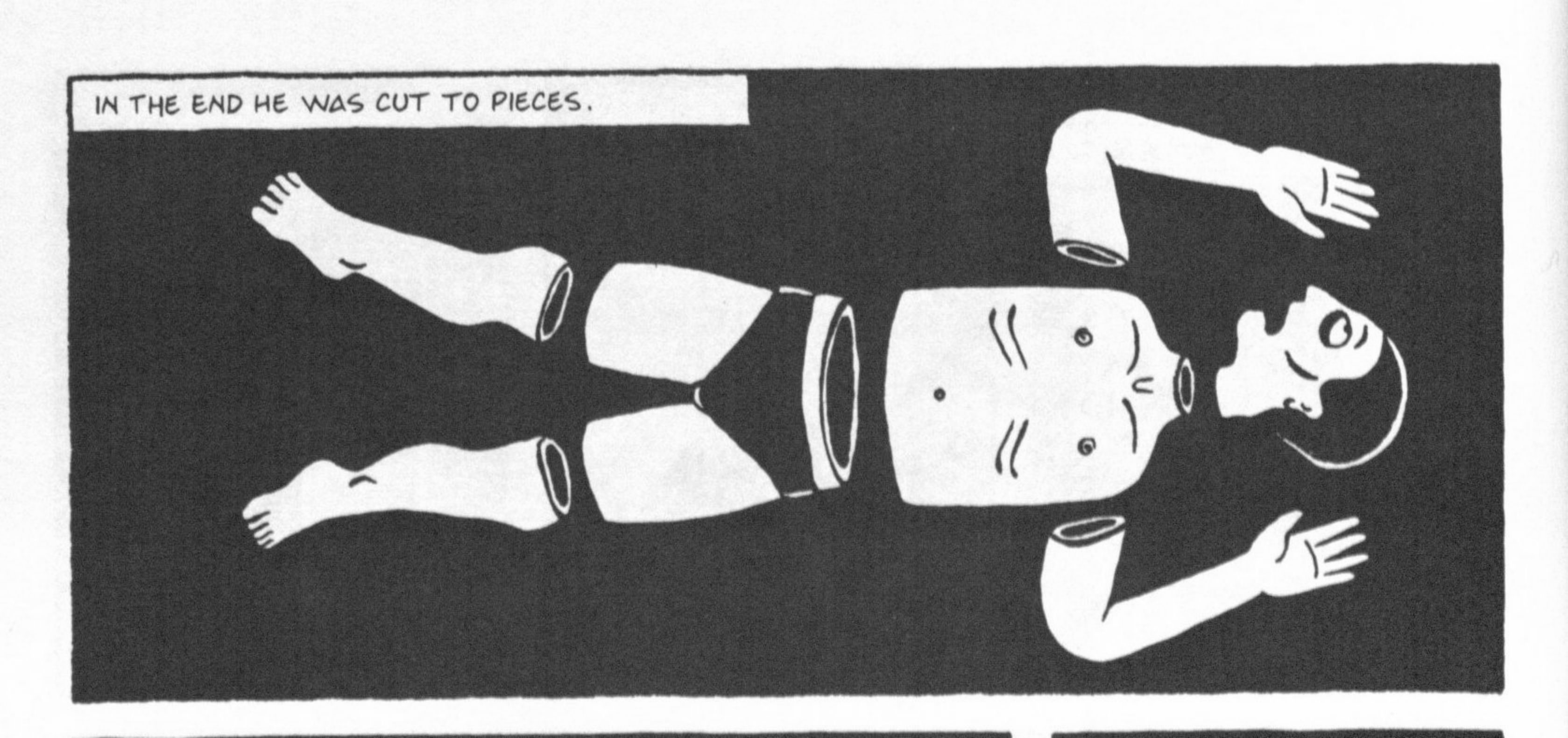

"I cannot take the idea of a man cut into pieces and just write it. It would not be anything but cynical. That's why I drew it."

The man looks like a doll taken apart. Perhaps this absurdity is the point. To cut a person up is to treat him like a doll, as if a person were a series of parts. But we are not dolls. We are living and a mess. Treating people like that IS absurd, best viewed from a stark and maybe childlike view. I think it's more like the child in "The Emperor's New Clothes." The child is the only one brave enough to tell the truth.

So, that's how I've come to respect Satrapi's style more.

Monday, November 12, 2012

Wednesday, November 7, 2012

Comics: Only for the smart people...that's YOU!

There are some fundamental questions that Maus asks about comics and history and what kind of history the two of them make together.

- How does the process of writing a history connect with the history itself?

- How accurate can any history be? What does the past mean in the present?

- What are autobiographical comics? Autobiographies? Biographies? Histories? Fiction? Does it matter? What happens when comics show history?

It's helpful to think of literature as having form and content. Content is the water, and the glass is the form. It's how you receive the content.

The form can change:

The form can change:

But the content is the same. Or is it? In the examples above, it doesn't exactly matter what you drink the water from, as long as you get the water. One glass is messier. One is taller, but it's not THAT big a deal.

Literature is more complicated because form and content work together. They are not just independent items mixed and matched like a rubik's cube. Some forms are difficult to drink from:

Others are not very appealing:

The form may actually enhance the content. It may change the content.

Comics are not glasses, nor is the content just some water, but we can see how form and content can have a complicated relationship. Comics are a form that affects the content of Maus and allows us a richer view of the Holocaust because it shows us how complicated and convoluted such histories are. Chute argues that "[comics] can make the twisting lines of history readable through form" (200) and that Maus in particular "engages [the ethical dilemma of writing history] through its form" (201).

I won't go into all of the arguments Chute makes to support this claim. Mostly, her close readings of scenes show us how two images appearing at once on the same page, crossing one another, next to one another, gives us a lot of VISUAL information about the difficulty of writing this history. We see how Spiegelman wants to make order out of Vladek's history while Vladek wants to get rid of it. We see how Art both pushes himself into the narrative and then feels like an imposter for trying to represent the Holocaust. We can also see how Maus shows the complicated nature of history itself, like Russian dolls:

Joshua Brown, who is quoted in Chute's article, says that "Vladek's account is not a chronicle of undefiled fact but a constitutive process, that remembering is a construction of the past" (qtd. in Chute 206). This is the point I tried to make in class on Monday. History is not simple, and the comic version might be the best way to show how un-simple it is, how many voices are really nested within the narrative. Here's another reminder from Spiegelman in the Chute article: "The number of layers between an event and somebody trying to apprehend that event through time and intermediaries is like working with flickering shadows" (qtd. in Chute qtd. in Brown--can I do that? :)

Joshua Brown, who is quoted in Chute's article, says that "Vladek's account is not a chronicle of undefiled fact but a constitutive process, that remembering is a construction of the past" (qtd. in Chute 206). This is the point I tried to make in class on Monday. History is not simple, and the comic version might be the best way to show how un-simple it is, how many voices are really nested within the narrative. Here's another reminder from Spiegelman in the Chute article: "The number of layers between an event and somebody trying to apprehend that event through time and intermediaries is like working with flickering shadows" (qtd. in Chute qtd. in Brown--can I do that? :)In other words, there is a LOT going on, and Maus is ABLE to show all the complications of this history, which make it far more than any movie or documentary or text memoir ever could. In fact, dare I say it, Maus is better at showing the Holocaust. Comics are the BEST choice.

Word.

So, let's keep this in mind as we read Persepolis, another historical memoir, this time an autobiography:

- Satrapi uses a very iconic style for her characters but she does not choose to make them into animals. How does this style work to her benefit? How does it detract from her narrative?

- There are not many ladies in the world of comics. How do you see gender represented differently in this comic? Find some examples.

- Check out the following pages in Persepolis: 61, 77, 102, 103.

Monday, October 29, 2012

Mausketeers

The world went nuts over Maus I and II; they fundamentally changed the scope of comics, much like Watchmen exploded our notions of superheroes. And, Art Spiegelman earned a tidy Pulitzer for his work in 1992, which earned him a spot in the canon of literature for a comic. It still is ground-breaking. The New York Times, which is often snooty about matters literary, noted Maus as "the important literary achievement of our age."

Let's look at some chronology:

1978--A Contract with God by Will Eisner is the first comic published as a "graphic novel"

1980-1985--first chapters of Maus appear in RAW, a comic run by Spiegelman

1986--Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (4-issue limited run series) by Frank Miller is published

1986-1987--Watchmen series is published by DC

This is just a brief survey of some fundamental texts happening at the same time. There are others, but each serves an interesting purpose. Will Eisner first calls something a graphic novel, which gives new critical credence to novel-length comics. He was also writing about the Jewish experience, which we'll see in Maus. The Dark Knight series reinvigorates an the superhero, while, soon after, Alan Moore attempts to explode the superhero genre completely. Maus came out during a very exciting time in the history of comics. Many ideas about comics changed at this time, though it took a while for this to hit the general public. Still, I mention Maus winning a Pulitzer and folks look at me like I've just started speaking in tongues. "Where's the translation??"

Maus was hard to write, as you can tell from the text. Spiegelman is open about his strained relationship with his father. According to Spiegelman, "The goal was to tell [Vladek's] story. And at a certain point, I went to see a shrink who had been a Holocaust survivor of Auschwitz, who helped me get past some [mental] blocks into the second volume...My shrink, he really liked the first book, and he was trying to get the second book out of me."

Because the medium (graphic novel) sits at the intersection between "serious" biographies/autobiographies/novels, it challenges our understanding of what it can do. Maus is simply labeled as a "A Survivor's Tale." Spiegelman is not really showing his cards with that moniker. Later, however, he writes in The New York Times, which has listed Maus under its fictional bestsellers:

http://digitalhistory.concordia.ca/courses/hist403w09/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/spiegelmannytletter.pdf

This series crosses from father to son, realism to strange iconography, and challenges what history is. This is fun stuff.

Here are some questions to consider this week as you finish up on the series:

- Why do you think Art Spiegelman chose the animals he did to represent different nationalities? What stereotypes do they convey?

- Consider this panel and talk about the design choices and textual choices Spiegelman made. How do both text and art come together? What would happen if they were separate?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)